Five Arts: Unveiling the Core of Chinese Metaphysics

Chinese metaphysics (中华玄学) boasts a profound history rooted in ancient China, where its core aim was to unravel the essence of reality. Generations of scholars and thinkers have delved deep into this study, decoding the universe’s intricate patterns and discerning their profound effects on human existence. While many associate Chinese metaphysics with Feng Shui, it’s essential to recognise that it encompasses a broad realm teeming with diverse practices and principles.

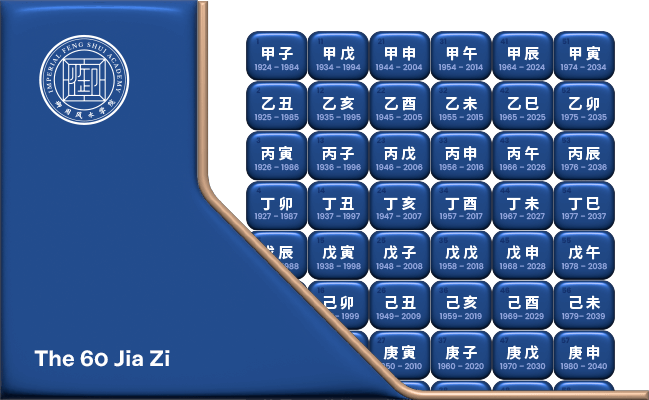

At the heart of this vast field lies the Five Arts (五术). These are not just abstract concepts; they represent five tangible and pivotal areas actively guiding our understanding of the universe. Drawing inspiration from the I-Ching (易經) or the Book of Changes, the Five Arts immerse us in ancient Chinese perspectives on time, space, and the vast cosmos, all the while resonating with the timeless balance of Yin and Yang. Early Taoist scholars played a crucial role in developing the Five Arts into a revered discipline.

What are the Five Arts?

The Five Arts (五术) of Chinese metaphysics are Mountain (山), Medicine (医), Divination (卜), Physical Inspection (相), and Destiny (命).

1. Art of Mountain

The art of Mountain encompasses disciplines designed to strengthen both the physical and mental aspects of being through nutrition, meditation, and martial arts. In the art of Mountain, diet is not just about sustenance but includes gathering wild edibles and maintaining a well-rounded diet to boost physical vigour and prevent diseases. Meditation employs focused contemplation to bolster mental strength. Intellectual stimulation and expansion of worldview come from delving into the works of ancient philosophers like Lao Zi (老子) and Zhuang Zi (庄子). Meanwhile, martial arts enhance mental acuity and contribute to an individual’s holistic development. Essentially, the art of Mountain is a confluence of techniques for nurturing a balanced and fully actualised individual.

Historically, the art of Mountain was seen as a journey towards self-betterment, where adepts would seclude themselves in the mountains, dedicating countless hours to developing their philosophies on Feng Shui, often in line with the wisdom of Chinese classics. Lu Ban (鲁班), an esteemed ancient Chinese figure in architecture and invention, found inspiration in nature, which informed his innovative work. His insights were later documented by historian Guo Pu (郭璞) in the seminal work “Book of Burial” 《葬书》, which outlined the tenets of geomancy and the criteria for selecting propitious locations for buildings and other significant sites.

The art of Mountain has deep roots in ancient China, with the earliest geomantic writings traced back to oracle bones from the Neolithic era, used to divine the most auspicious burial locations. The practice evolved into what is known today as Feng Shui during the Qin dynasty, focusing on the siting of structures and tombs.

In the Tang dynasty, Feng Shui reached its zenith, guiding the placement of capitals, royal residences, and temples. Yang Yun Song (楊筠松), a prominent figure of the era, authored pivotal texts on Feng Shui, setting a standard that would influence Imperial studies of the discipline through successive dynasties, including Tang, Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing.

In the contemporary world, Feng Shui has transitioned from a practice centred around grave sites to a holistic discipline that informs the creation of balanced living and working spaces. Modern practitioners may integrate aspects like colour theory and energy dynamics in their practice, while the core principles of geomancy continue to play a significant role in urban development and architectural design.

2. Art of Medicine (医)

The art of Medicine refers to the study and practice of traditional Chinese medicine. It delves into matters of health, focusing on methods of curing diseases, ailments, and physical diagnosis. Within this study, the principles of Qi, Yin and Yang, and the Five Elements underpin a practitioner’s understanding of an individual’s health and well-being. While its research and studies are strongly linked to the Bagua (八卦), I-Ching, and the relationships between the Five Elements, examples of its methods include Traditional Chinese Medicine, acupuncture (针灸), and herbal medicine (草药).

History of Medicine in Ancient China

During the Warring States period (476 to 221 BC), several schools of thought emerged regarding the art of Medicine, including the “Yellow Emperor’s Inner Cannon”《黄帝内经》—an ancient Chinese medical text highly respected as the fundamental source for doctrines in Chinese medicine for more than two millennia. The work establishes the theoretical basis of traditional Chinese medicine, and its diagnostic methods, and discusses acupuncture.

In the Han dynasty (202 BC to 9 AD, 25 to 220 AD), acupuncture and herbal medicine became prominent methods of medical treatment and maintaining health. Zhang Zhongjing (張仲景), a Chinese pharmacologist and eminent physician, authored “Treatise on Cold Pathogenic and Miscellaneous Diseases”《伤寒杂病论》—a foundational text for the advancement of Chinese medicine.

The Tang dynasty saw the emergence of pulse diagnosis as a diagnostic method in Chinese medicine, alongside the use of moxibustion in treating ailments. Sun Simiao (孙思邈), a physician and Taoist monk, authored the “Essential Formulas Worth a Thousand in Gold for Emergencies”《備急千金要方》—detailing medical disorders, diagnoses, treatments, and remedies.

The publication “Compendium of Materia Medica”《本草纲目》compiled by Li Shizhen (李时珍) during the Ming dynasty (1368 to 1644 AD)—an encyclopedic gathering of knowledge surrounding Chinese medicine, natural history, and herbology—became the foundation for what is recognised today as traditional Chinese medicine.

Modern Applications for the Art of Medicine

Today, traditional Chinese medicine is widely practised worldwide, with treatments including herbal remedies, acupuncture, moxibustion, cupping, and Tui Na massages. As an alternative medical practice, traditional Chinese medicine has been the subject of research and clinical trials, investigating its efficacy for conditions such as chronic pain, infertility, and cancer.

3. Art of Divination (卜)

The art of Divination has a long history in Chinese metaphysics, widely used by prominent military and political figures, such as Zhuge Liang (诸葛亮), Li Chunfeng (李淳风), Liu Bowen (刘伯温), and Zeng Guofan (曾国藩), to strategise their victories. According to ancient texts, this art form manifests in three main methods: fortune-telling, auspicious date selection, and the analysis of the cosmic flow of energy.

History of Divination in Ancient China

According to Chinese legends and mythology, Fu Xi (伏犧) is credited with the creation of the I-Ching, setting the foundation for Chinese divination practices. During the Zhou dynasty (1046 to 256 BC), the I-Ching was refined as a divination tool, and Confucius (孔子) later philosophised that the I-Ching was a tool for personal reflection and ethical guidance. The Qin dynasty outlawed divination, but it continued to be practised underground.

In the Tang dynasty (618 to 907 AD), divinatory arts saw a resurgence, with the reintroduction of various forms of divination such as Na Jia divination (纳甲筮法), Plum Blossom Divination (梅花易数), and the Three Styles—Liu Ren (六壬), Tai Yi Divine Numeration (太乙神数), and Qi Men Dun Jia (奇门遁甲). Under Emperor Taizong’s rule, advancements in divination occurred, resulting in the publication of the treatise “Early Heaven Bagua”《先天八卦》based on the I-Ching.

Modern Applications for the Art of Divination

While divination methods remain widely used today for personal guidance, some techniques have been adapted for contemporary use in business and finance. For example, Qi Men Dun Jia (奇门遁甲) is used for making business, trade, or investment decisions, and in career or academic pursuits. This tool utilises astronomical observation and various aspects of Chinese metaphysics to create strategies and solutions.

4. Art of Physical Inspection (相)

The study of Physical Inspection refers to the inspection of physical forms or appearances, including different categories of physical inspection:

- 名相 (míng xiāng): Examination of an individual’s or shop’s name through the analysis of the Five Elements and other divination techniques.

- 印相 (yìn xiàng): Observation of an individual’s seal to determine their destiny.

- 家相 (jiā xiāng): Analysis of a home’s layout to determine the quality of its Feng Shui.

- 墓相 (mù xiāng): Placement of ancestral tombs to ensure good fortune for future generations.

- 人相 (rén xiāng): Reading an individual’s physical appearance to gain insight into their personality and potential, encompassing practices like palmistry and face reading.

History of Physical Inspection in Ancient China

The earliest known writings on Physical Inspection date back to the Shang dynasty. During the Qin dynasty, Physical Inspection practices were associated with superstition and were prohibited. In the Zhou dynasty, Guan Zhong (管仲), a philosopher and chancellor, was known for physiognomy—reading an individual’s personality through their appearance. Dong Zhongshu (董仲舒), a philosopher and politician, authored “Luxuriant Dew of the Spring and Autumn Annals” 《春秋繁露》, including teachings on physiognomy and its use in selecting capable government officials. The Song dynasty (960 to 1279 AD) saw the peak of Physical Inspection methods, developing the “Three Physiognomies” system using facial features, body shape, and mannerisms to determine an individual’s character and potential.

Modern Applications for the Art of Physical Inspection

The principles of Physical Inspection are still widely used today, with contemporary practitioners adapting techniques for use in fields such as business and dating. Even facial recognition technology in law enforcement, marketing, or technology fields could be seen as a contemporary application of physiognomy.

5. Art of Destiny (命)

The art of Destiny refers to the study of fate calculation, exploring the influence of cosmic forces on people’s fates and fortunes. Destiny practices have been extensively observed throughout documented Chinese history, used by members of the ruling elite and nobility to provide guidance and insight into their strengths, weaknesses, and potential for success.

History of Destiny in Ancient China

Astrology, a major component of Destiny practices, developed during the Western Zhou dynasty (1045 to 771 BC) as a method for future prediction and determining auspicious calendar dates. In the Han dynasty, the Four Pillars of Destiny (八字) system emerged, using birth information and location to determine fate. Emperor Wu of the Han dynasty consulted astrologers and diviners, developing the Nine Star Qi (九星气学) system alongside astrology.

Purple Star Astrology (紫微斗数) emerged during the Tang Dynasty, further developed by Chen Xi Yi (陳希夷) during the Song Dynasty and Luo Hong Xian (罗洪先) in the Ming Dynasty. The Ming dynasty also produced prominent figures like Liu Bowen, a military strategist and philosopher, known for divination and destiny analysis, and Jiang Da Hong (蒋大鸿), a Taoist master who authored “The Secret of the Golden Flower”《太乙金華宗旨》, including teachings on astrology and Bazi.

Modern Applications for the Art of Destiny

Today, the art of destiny analysis helps individuals pursue abundance, prosperity, and progress. Renowned methods like Bazi (八字) and Purple Star Astrology (紫微斗数) are widely adapted for use in Feng Shui analyses, business and marketing consulting, and life coaching.

The Five Arts Today

The Five Arts form an integral branch of Chinese metaphysics, with unique histories, developments, and applications as detailed as that of Chinese civilisation itself. Today, the Five Arts have evolved and adapted to contemporary lifestyles, continuing to provide a comprehensive understanding of the universe and our place within it.

Mastering the Five Arts can offer profound insights and practical applications for achieving balance, prosperity, and well-being in various aspects of life. Whether through the practice of Feng Shui, traditional Chinese medicine, divination, physical inspection, or destiny analysis, these ancient arts remain relevant and influential in modern times.