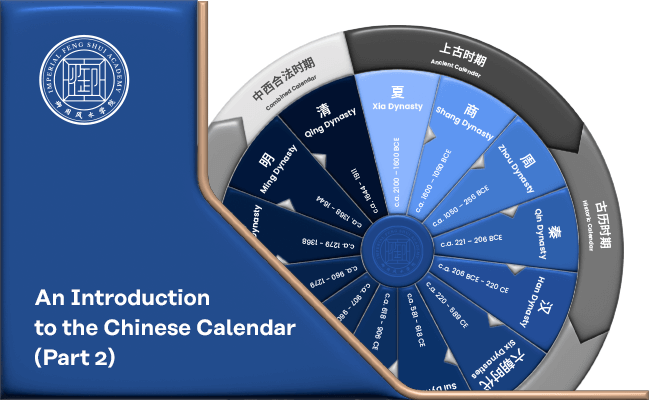

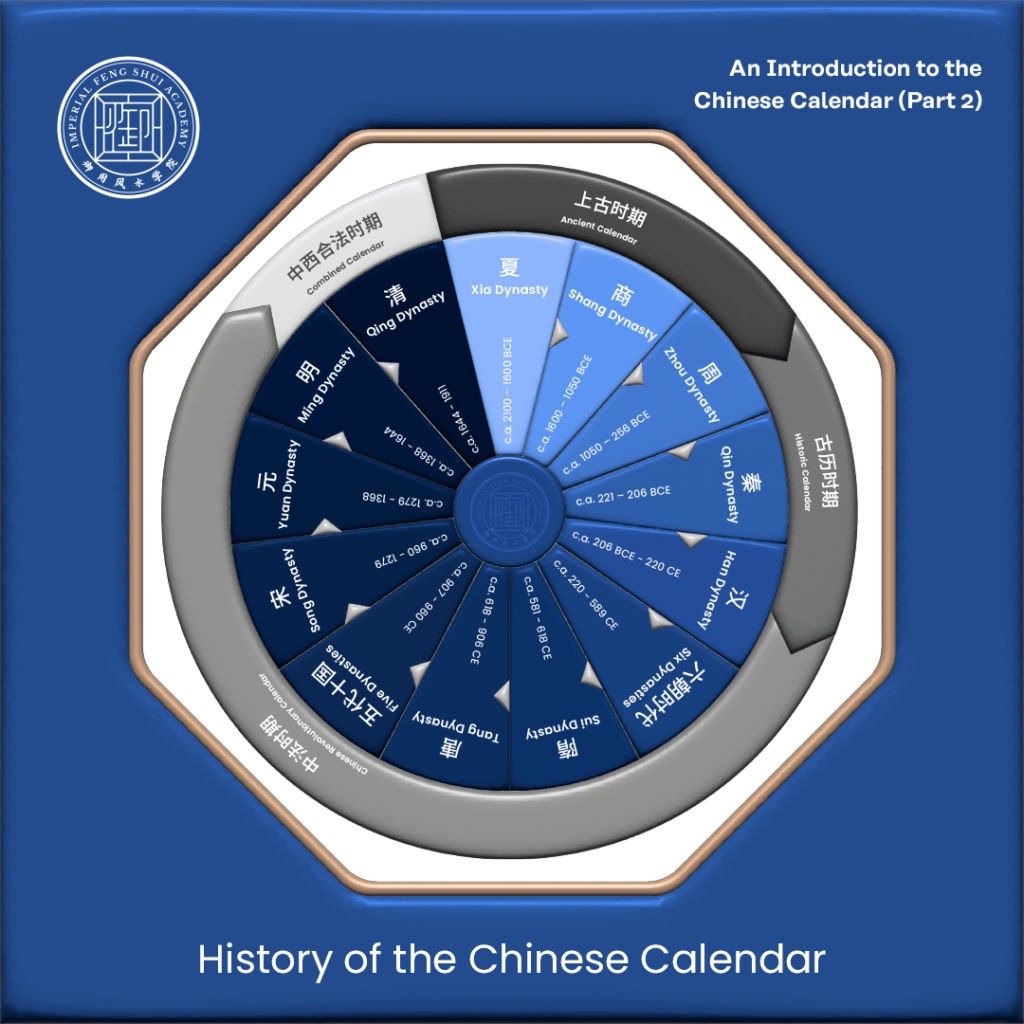

The Chinese calendar has a profound influence on Chinese society, guiding holiday traditions and contributing to the understanding of Chinese metaphysics and Imperial Feng Shui. In the previous article, we explored the early development of Chinese calendar systems during the Ancient Calendar period (上古时期), which included the Xia, Shang, and early Zhou dynasties (2070 to 771 BC). We also delved into the Historic Calendar period (古历时期), covering the Warring States period, the Qin, and Han dynasties (476 BC to 220 AD).

In this article, we will examine the evolution of the Chinese calendar during the Chinese Revolutionary Calendar period (中法时期) and the Combined Calendar period (中西合法时期). These advancements have significantly shaped the modern Chinese calendar through meticulous astronomical observations and research over centuries.

Chinese Revolutionary Calendar Period (中法时期)

The Chinese Revolutionary Calendar period spans the Han and Ming dynasties (202 BC to 1644 AD). A notable event during this period was the reformation of the calendar by Emperor Wu of Han (汉武帝), leading to the creation of the Taichu Calendar.

Taichu Calendar Reformation

Emperor Wu of Han identified inaccuracies in the existing Zhuān Xū Calendar and, with advice from court officials, appointed astronomer Deng Ping (邓平) to compile a new calendar using the 81 Rule (八十一分律历). This rule calculated a month as 29 and 43/81 days, resulting in the “81-point law calendar,” known as the Taichu Calendar. This calendar improved the accuracy of astronomical observations, particularly solar and lunar eclipses.

The Three System Calendar (三统历)

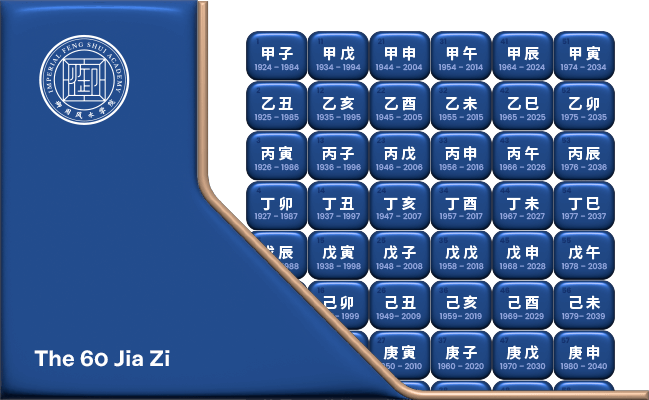

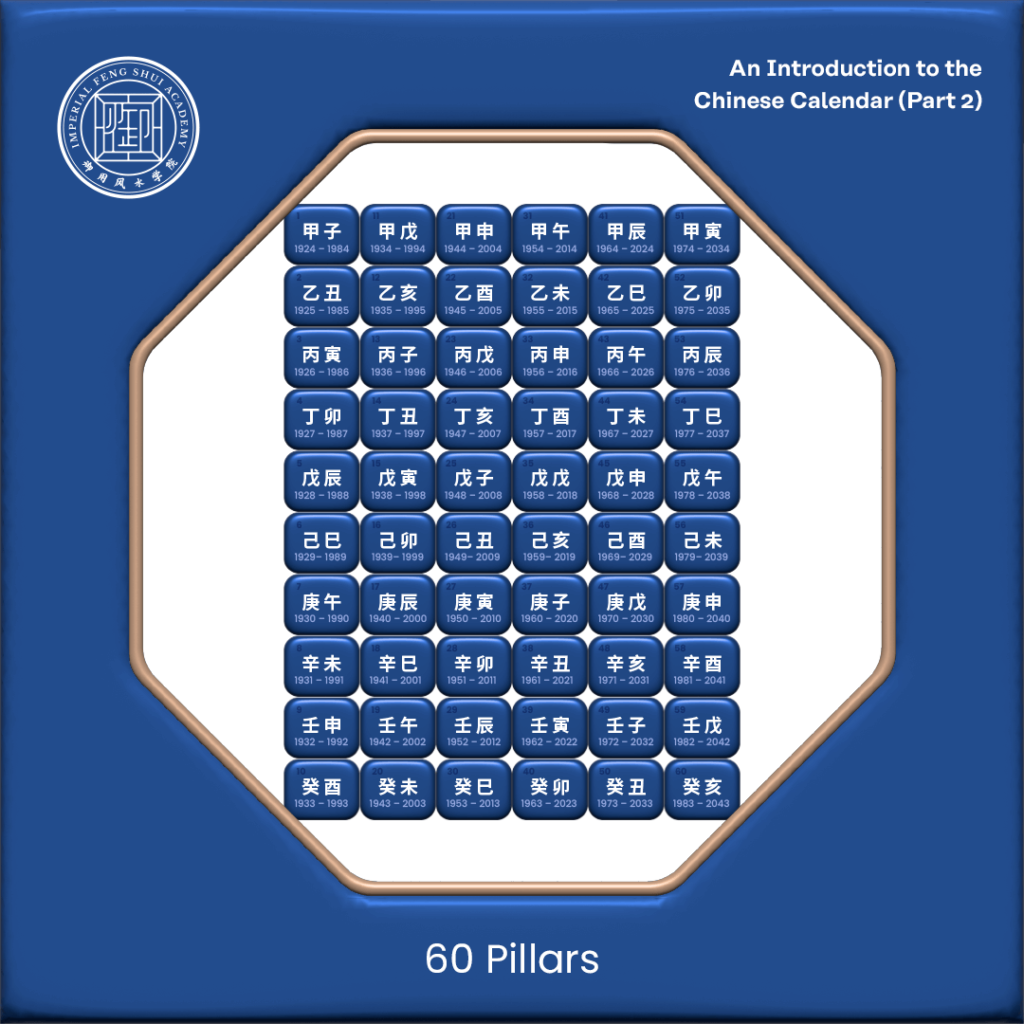

During the Han dynasty, mathematician and astronomer Liu Xin (刘歆) proposed enhancements to the Taichu Calendar. His improvements, based on additional astronomical theories and observations, were documented in the “Book of the Three System Calendar” (三统历谱). This calendar system integrated the sexagenary cycle (六十干支), a 60-year cycle based on the Ten Heavenly Stems and Twelve Earthly Branches. Despite its accuracy, the Three System Calendar ceased usage around 84 AD.

Yuan Jia Calendar (元嘉历)

During the Northern and Southern dynasties, Emperor Wen of Song (宋文帝) introduced the Yuan Jia Calendar, compiled by astronomer He Tian Cheng (何天承). This calendar incorporated the Five Stars (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn) in its calculations, enhancing predictive accuracy.

The Twelve Qi Calendar (十二气历)

By the Song dynasty (960 to 1279 AD), there were 18 calendar calculation methods in use. Scientist Shen Kuo (沈括) introduced the Twelve Qi Calendar to address discrepancies within the existing systems. This calendar matched months to 12 main solar terms, aligning with the 12 Earthly Branches and improving agricultural productivity.

The Twelve Qi Calendar’s Solar Terms

| Earthly Branch (地支) | Solar Term (Chinese) | English Name | Approximate Gregorian Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| 寅 (Yin) | 立春 (lì chūn) | Start of Spring | February 4th |

| 卯 (Mao) | 惊蛰 (jīng zhé) | Waking of Insects | March 6th |

| 辰 (Chen) | 清明 (qīng míng) | Clear and Bright | April 5th |

| 巳 (Si) | 立夏 (lì xià) | Start of Summer | May 5th |

| 午 (Wu) | 芒种 (máng zhòng) | Grain in Ear | June 6th |

| 未 (Wei) | 小暑 (xiǎo shǔ) | Lesser Heat | July 7th |

| 申 (Shen) | 立秋 (lì qiū) | Start of Autumn | August 8th |

| 酉 (You) | 白露 (bái lù) | White Dew | September 8th |

| 戌 (Xu) | 寒露 (hán lù) | Cold Dew | October 8th |

| 亥 (Hai) | 立冬 (lì dōng) | Start of Winter | November 7th |

| 子 (Zi) | 大雪 (dà xuě) | Great Snow | December 7th |

| 丑 (Chou) | 小寒 (xiǎo hán) | Lesser Cold | January 6th |

Combined Calendar Period (中西合法时期)

The Combined Calendar period marks the integration of Western scientific methods into Chinese calendrical calculations during the transition from the Ming to the early Qing dynasty. Jesuit missionaries introduced Western astronomy concepts, leading to advanced calendars blending Chinese and Western techniques.

The Xiao An Calendar and Time Regulated Calendar

Astronomer Wang Xishan (王锡阐) developed the Xiao An Calendar (晓庵历), incorporating Western scientific concepts. Although it was not implemented due to political reasons, the Qing dynasty later adopted the Time Regulated Calendar, which combined the Xia Calendar methods with Western research. The Time Regulated Calendar, revised with Isaac Newton’s Theory of the Moon’s motion during Emperor Qian Long’s reign, continues to be in use today as the Chinese Traditional Calendar.

Significance of the Chinese Calendar in Imperial Feng Shui

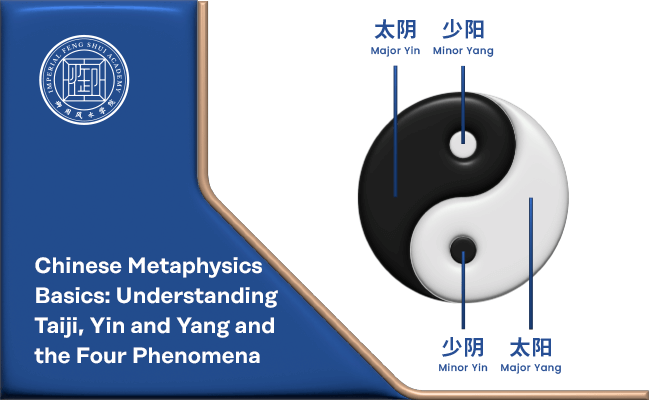

The Chinese calendar is fundamental to Chinese metaphysics and Imperial Feng Shui practices, such as Bazi (八字) and auspicious date selection.

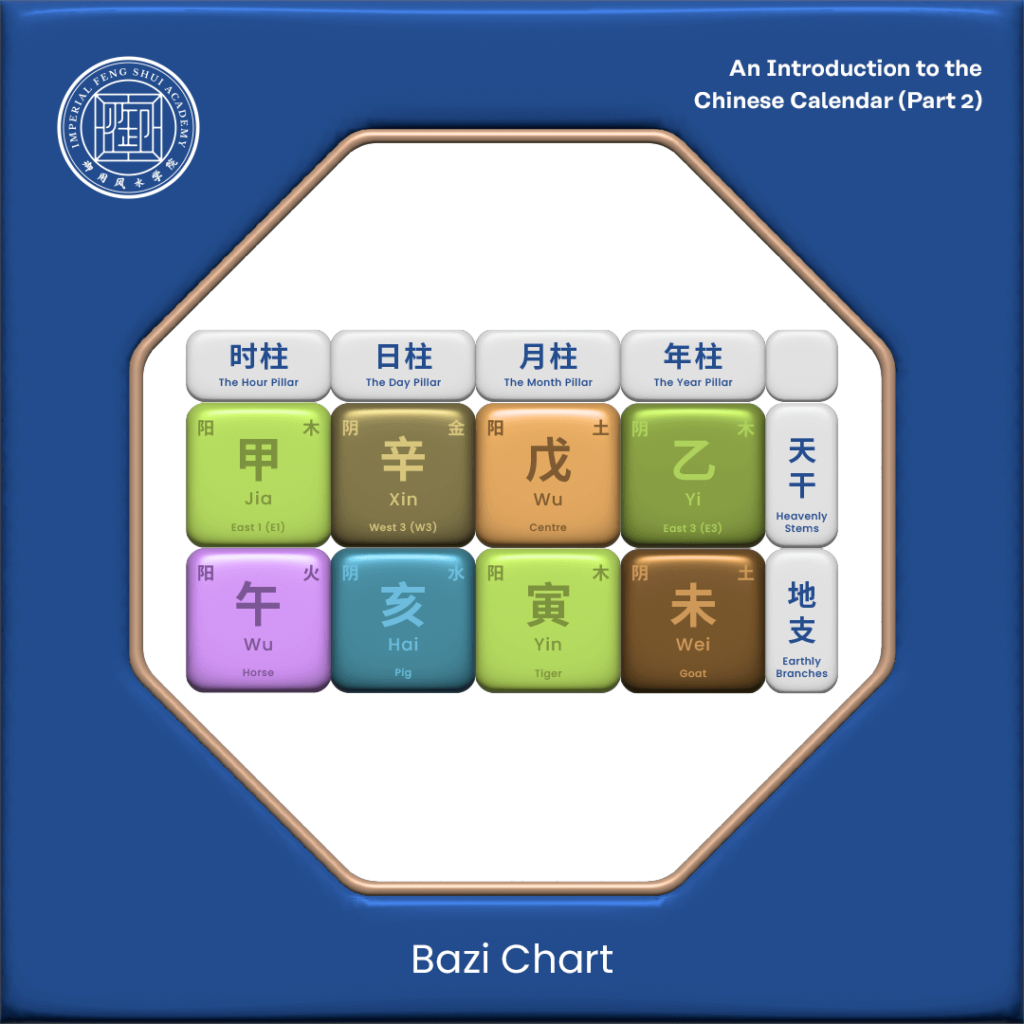

Bazi (八字)

Bazi, or Four Pillars of Destiny, uses the Chinese calendar to interpret an individual’s destiny based on their birth year, month, date, and hour. Each Bazi chart comprises the Ten Heavenly Stems and Twelve Earthly Branches, structured according to the Four Pillars:

- Year Pillar (年柱)

- Month Pillar (月柱)

- Day Pillar (日柱)

- Hour Pillar (时柱)

Understanding Bazi helps individuals navigate their strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and risks, fostering success in personal and professional endeavours.

Auspicious Date Selection

Selecting auspicious dates is crucial for ensuring favourable outcomes in significant events and activities. The Chinese calendar underpins this practice, with Bazi dynamics playing a large role in personalizing date recommendations.

The evolution of the Chinese calendar is a testament to the meticulous astronomical observations and scientific advancements made over centuries. From the Taichu Calendar’s inception to the integration of Western methods, each period contributed to the calendar’s accuracy and relevance. Today, the Chinese calendar remains a cornerstone of Chinese culture, influencing holiday traditions, agricultural practices, and metaphysical studies like Bazi and Feng Shui. Understanding this calendar not only provides insight into historical advancements but also enriches the appreciation of its ongoing significance in contemporary Chinese society.