The Chinese calendar, also known as the lunar or Xia calendar (夏历), is a vital part of Chinese culture, used for determining dates and celebrating traditional holidays. Despite the widespread use of the Gregorian calendar in modern China, the Chinese calendar retains significant cultural importance. This lunisolar calendar, similar to the Babylonian, ancient Indian, and Jewish calendars, combines lunar months with the solar year, blending the cycles of the moon and the sun.

The Historical Development of the Chinese Calendar

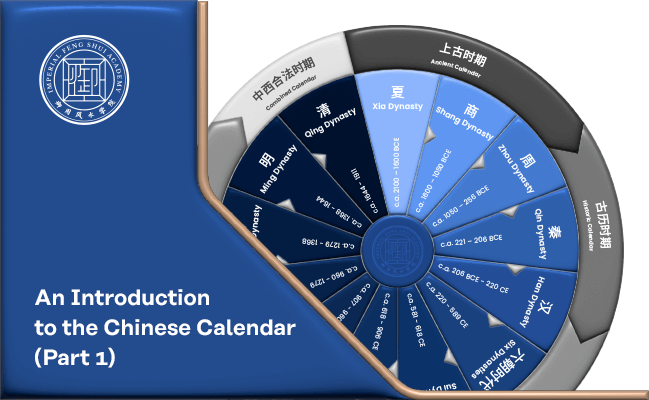

The roots of the Chinese calendar go back to the early Zhou dynasty (771 to 256 BC). Through centuries of astronomical observations and refinements, it evolved into the precise system in use today. The evolution of the Chinese calendar can be divided into four significant periods:

Ancient Calendar Period (上古时期)

Dynasties: Xia, Shang, and early Zhou (2070-771 BC)

Summary: This era laid the foundational work for the calendar through intensive astronomical research and observation.

Historic Calendar Period (古历时期)

Dynasties: Warring States, Qin, and Han (476 BC-220 AD)

Summary: Six primary calendar systems were developed, including the Yellow Emperor Calendar (黄帝历) and Zhuān Xū Calendar (颛顼历), among others.

Chinese Revolutionary Calendar Period (中法时期)

Dynasties: Han and Ming (202 BC-1644 AD)

Summary: Major reforms were introduced, such as the Taichu calendar reform by Emperor Wu of Han. Despite various developments, the core principles remained consistent.

Combined Calendar Period (中西合法时期)

Dynasties: Ming and Qing (1368-1912 AD)

Summary: The introduction of Western scientific methods led to calendars that blended Chinese and Western techniques.

In this article, we focus on the early stages of the Chinese calendar’s development, particularly the Ancient and Historic periods.

Ancient Calendar Period

The Ancient Calendar period marks the inception of early calendar systems during the Xia (2070-1600 BC), Shang (1600-1046 BC), and Zhou dynasties (1046-256 BC). For early Chinese societies, understanding natural cycles was crucial for agricultural planning. Observing the sun, moon, bird migrations, and seasonal changes helped them develop concepts of years, months, and days.

One of the earliest scientific documents from this era is “夏小正” (xià xiǎo zhèng), written during the Xia dynasty. This document detailed the Big Dipper’s constellations as monthly indicators and is believed to mention the Winter Solstice (冬至) and the 24 solar terms for the first time. Oracle bones from the Yin people, who later founded the Shang dynasty, referred to the moon’s phases, linking them to climate and star movements, thus documenting early lunisolar calendar methods.

Artefacts from the Zhou dynasty reveal an advanced understanding of lunar phases and calendar calculations. Written records, poetry, and prose from this period discuss planetary movements, such as Venus (金星). Zhou astronomers refined their knowledge of lunar phases, leading to updates of existing lunar calendars.

Historic Calendar Period

During the Historic Calendar period, six main calendar systems were established from the Warring States period (476-221 BC) through the Qin (221-206 BC) and Han dynasties.

The Warring States period saw significant progress in calendar development. Numerous revisions led to various named months, dates related to heavenly stems and earthly branches, and recorded eclipses. By 589 BC, solar eclipses (日食) and new moons (朔日) were integrated into calendar calculations, leading to the adoption of the 19 Years and 7 Leap Months (十九年七闰月) lunisolar system.

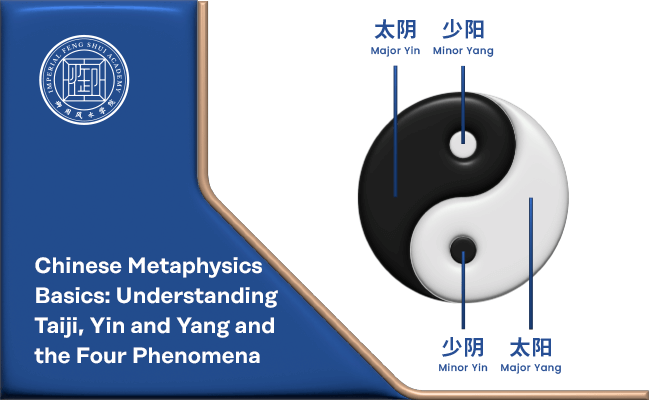

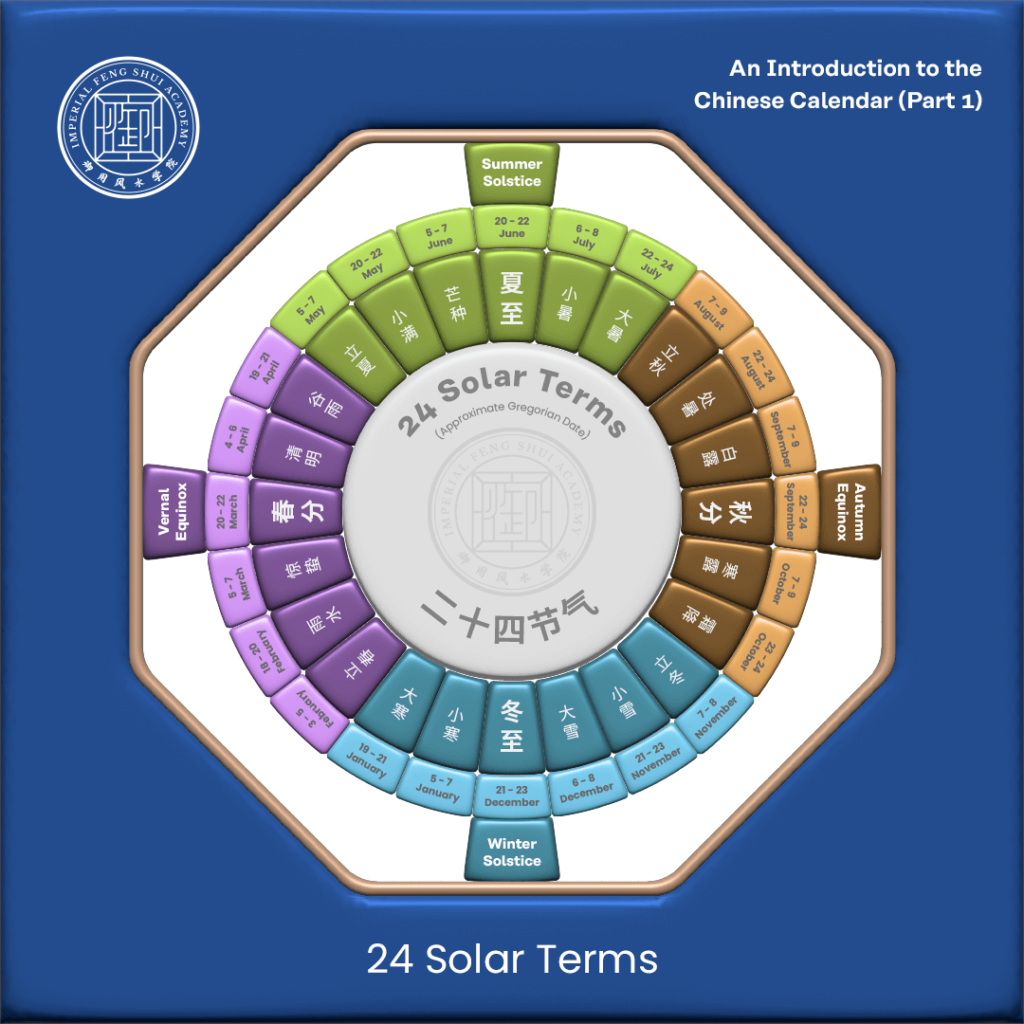

The lunisolar calendar, also known as the farmer’s calendar (农历) or Yin calendar (阴历), combines lunar and solar systems to account for both the moon’s orbit around the earth and the earth’s orbit around the sun. It guided agricultural activities in ancient China, dividing the solar year into 24 solar terms (二十四节气) to aid farming communities.

During the Han dynasty, the “汉书·艺文志” (hàn shū yì wén zhì) documented six primitive lunisolar calendars: Yellow Emperor Calendar (黄帝历), Zhuān Xū Calendar (颛顼历), Xia (Hsia) Calendar (夏历), Yin Calendar (殷历), Zhou Calendar (周历), and Lu Calendar (鲁历).

The Qin dynasty introduced a calendar incorporating the Five Elements (五行), known as the Zhuān Xū calendar, later modified by the Han dynasty. However, the Xia calendar, marking the Spring Equinox as the start of the year, became more prominent due to its agricultural relevance.

The Xia Calendar (夏历)

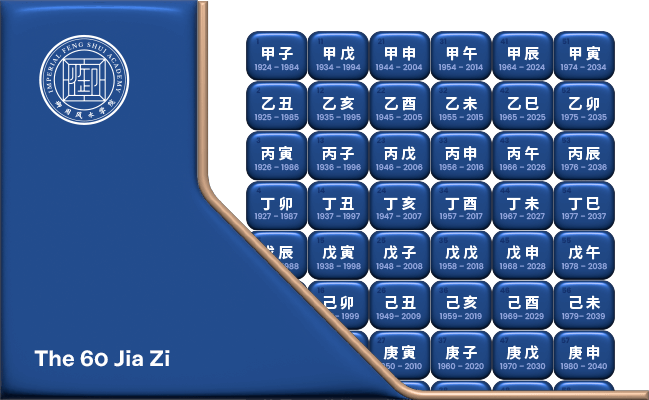

The Xia calendar, or Ten Thousand Year Calendar (万年历), operates on a sexagenary cycle (六十干支) based on 60 combinations of Ten Heavenly Stems and 12 Earthly Branches. Originating in the Xia dynasty, this calendar designates the new moon as the first day of the month, with the 15th day as the full moon. Each month is named according to the 12 Earthly Branches and is divided into two sub-months, reflecting seasonal changes.

The Xia calendar is used to map an individual’s Bazi (八字), determining the Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches in each chart. Its precision in predicting energy movements is fundamental to many Feng Shui practices, influencing Xuan Kong Flying Star Feng Shui, San He Feng Shui, Bazi, and auspicious date selection.

The Chinese calendar has significantly impacted Chinese metaphysics, especially in Imperial Feng Shui concepts like Bazi and auspicious period determinations. In the next part, we will explore how the Chinese calendar evolved into its modern form.